From the second half of the 19th century onwards, cannabis entered all European pharmacopoeias without any hesitation on the part of health authorities, until the mid-20th century when it was demonized and prohibited for supposedly “corrupting,” according to the ruling powers of the time, Black and Hispanic people.

Hemp did not adapt well to the requirements of the Industrial Revolution, as there was no technological development of machinery for its harvesting until well into the 20th century that could reduce labor costs.

By the end of that century, ship ropes began to be made of wire cable, and with the appearance of steamships, hemp sails disappeared.

From pharmacy shelves to demonization

From the second half of the 19th century onwards, cannabis entered all European pharmacopoeias without any hesitation from health authorities. But by the end of the 19th century, with the development of synthetic substances such as aspirin and barbiturates, which at that time were chemically more stable and reliable than cannabis, the decline of cannabis as a pharmaceutical product accelerated. International control of cannabis began at the 1925 Geneva Convention.

In early 20th-century American society, the press magnate William Randolph Hearst (1863–1951), whom we could call public enemy number one of our beloved plant, used all his media outlets to publish sensationalist and completely unsubstantiated articles claiming that Black people and Mexicans became depraved beasts under the influence of “marijuana.”

Hearst deliberately used the word “marijuana” instead of “hemp” or “cannabis” so that his readers would not realize what substance was being referred to. In short, as we can see, he was a true precursor of what we now call “Fake News.”

His sensationalist campaigns influenced the prohibition of hemp. The little information about cannabis at that time came from Hearst’s local sensationalist newspapers. Between 1916 and 1937, a car accident where a cannabis joint was found would dominate the headlines for weeks; Mexicans were falsely accused of spreading the vice among young people at school gates, and so on.

Continuing in this climate of demonization, in 1936 the film director Dwain Esper released Marihuana. The film told the story of young people who smoked it and then turned to crime, sinfully bathing naked.

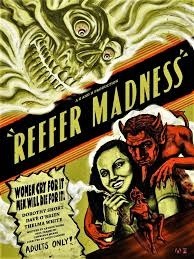

Another film from that same year, 1936, was Reefer Madness, directed by Louis Gasnier. It was produced as part of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics campaign. The movie depicted a group of young people who, after trying marijuana, committed murders, turned to prostitution, rape, terrorism, and suicide.

Both films were nothing but nonsense lacking rigor and truth—in short, pure propaganda garbage—that gradually shaped public opinion at the time, generating a completely anti-cannabis movement.

And then came prohibition

Given these public opinion winds, in 1937 the United States prohibited cannabis for any purpose. It is also worth noting that there were many other factors that caused cannabis to fall into disgrace and be eliminated from the market.

By around 1933, alcohol had been re-legalized in the United States, and most police forces were about to be left without work. The prohibition of cannabis served as an excuse to keep them employed.

The petrochemical industry eliminated the need for cannabis as a raw material, and wood fiber replaced hemp in paper production. In short, powerful lobbies in the cotton, timber, and the emerging chemical and petroleum industries did everything possible, using Hearst’s media outlets, to get rid of troublesome cannabis.

It was also eliminated from all pharmacies in the country, replaced by new drugs such as barbiturates or benzodiazepines, which the pharmaceutical lobby wanted to establish as dominant.

Worldwide prohibition was achieved in 1961 with the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. In the following twenty-five years, legislation was enacted to completely eliminate cannabis use worldwide.

Now winds of openness are blowing?